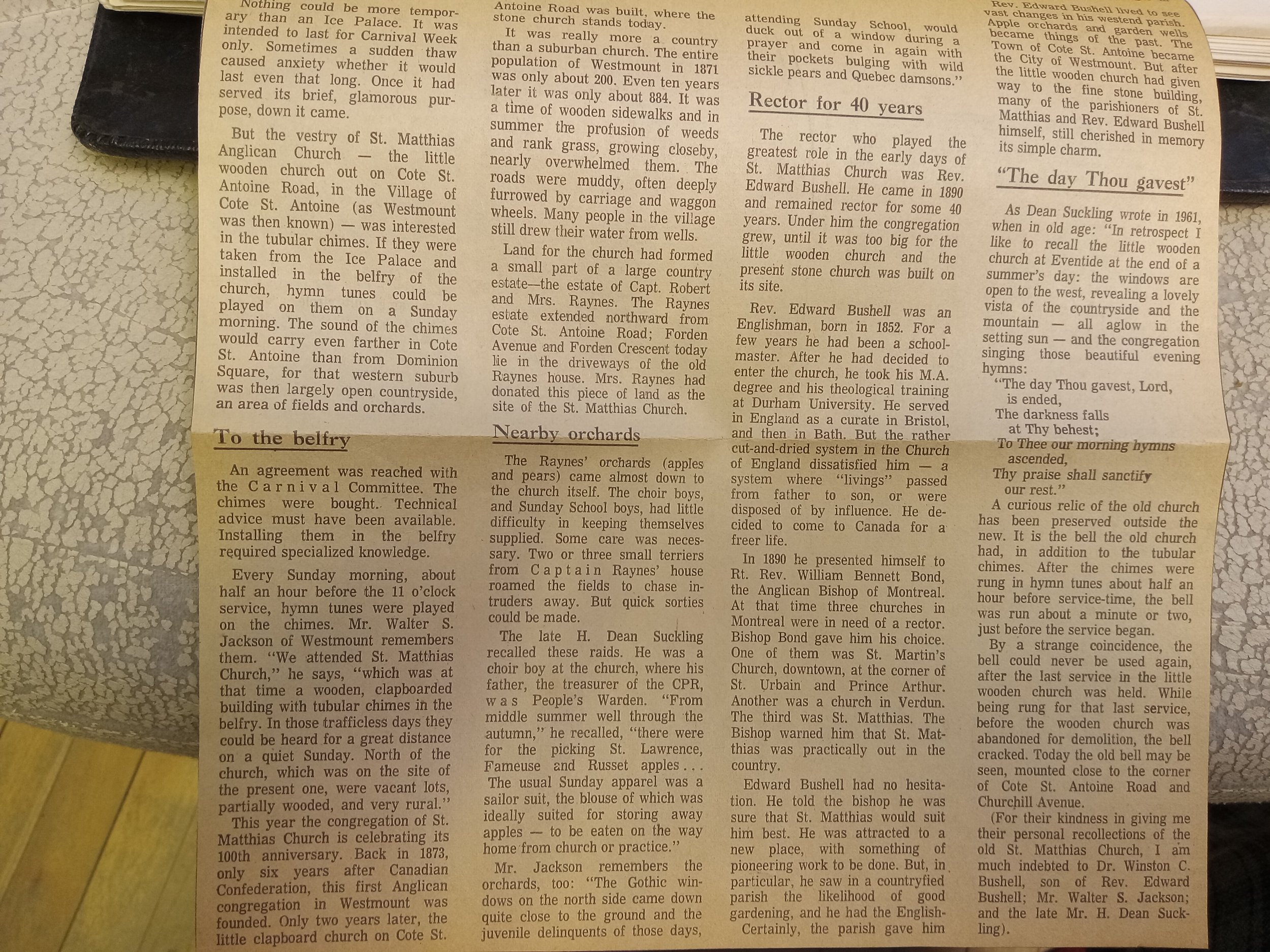

August 13th: The Chimes

St. Matthias’ was officially founded as a mission of St. George’s, Place du Canada, in 1873, which means our community is 150 this year! For the next 12 months, we’ll be diving into the archives to shine the spotlight on particularly interesting parts of our history.

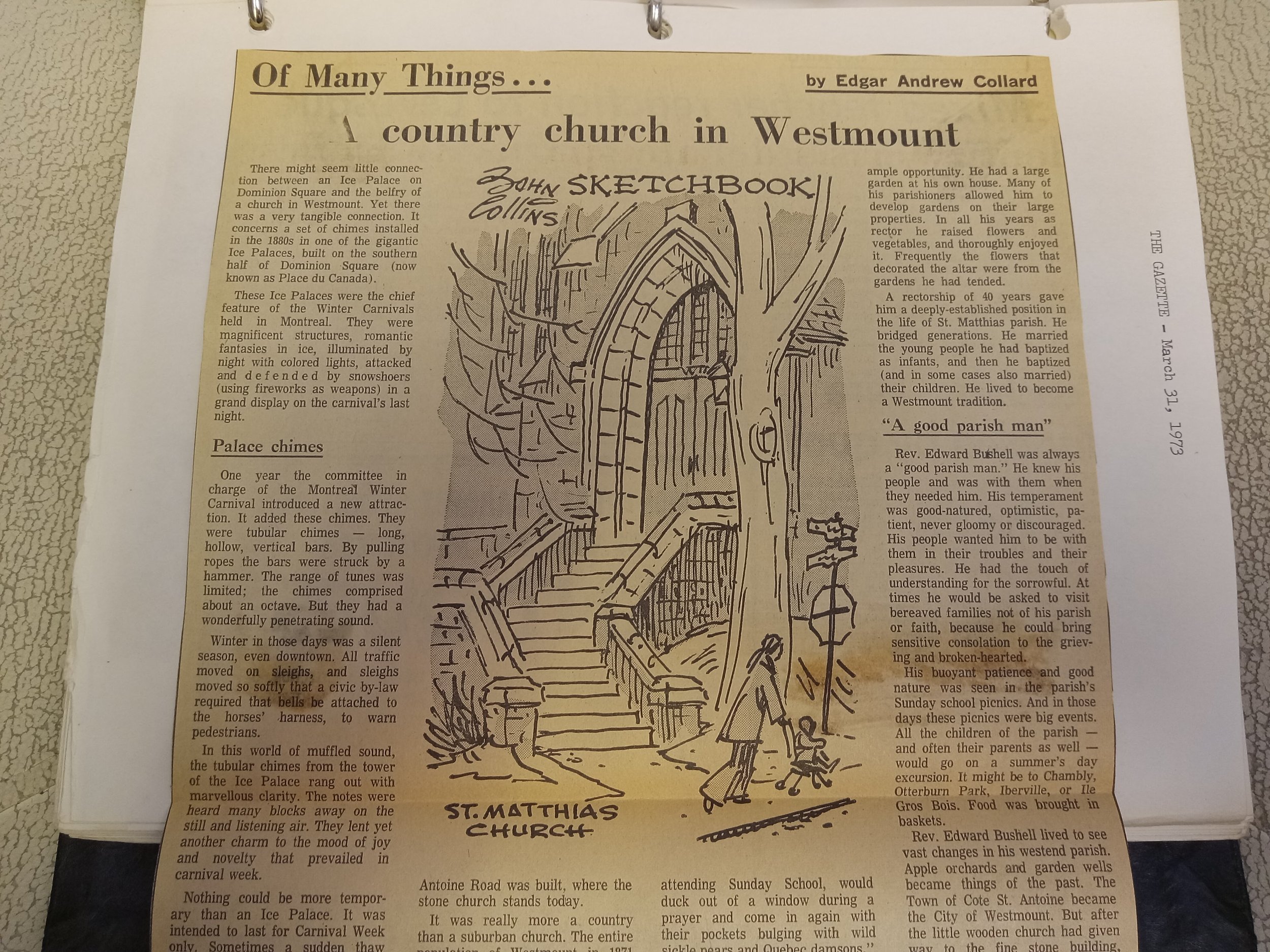

A photograph from 1884 of Montreal’s Winter Carnival Ice Palace, taken from the McCord Museum collection. The inscription reads: ICE PALACE, WINTER CARNIVAL, MONTREAL, 1884, / GREATEST LENGTH, 160 FEET; DEPTH, 65 FEET; MAIN TOWER, 76 FEET HIGH; BUILT OF BLOCKS OF ICE ABOUT 40 x 20 INCHES.

In the 1880s, Montreal (population: 217,000 by 1891) faced the harshness of winter in a quintessentially Victorian English way: by building vast architectural confections out of snow. The first Ice Palace was designed for 1883’s Winter Carnival by A.C. Hutchinson, an architect who had made a name for himself helping with Christ Church Cathedral when he was just 19, and who would go on to help design the Canadian Parliament. He treated ice like stone, ordering it chipped out of the St. Lawrence River in 500-pound blocks to be assembled into a 100-foot-high monstrosity that would be carved to resemble the Gothic Revival architecture that was currently all the rage. On the last day of the festival, the city’s many snowshoe clubs laid siege to the Ice Palace with fireworks (defenders inside used the same weapons), bringing the Carnival to a spectacular end. The feat was repeated every year until the Carnival was discontinued in 1889.

Although the point of the tourist-oriented Carnival was to put Montreal’s winter sports on display, the physicality of the event was tempered, starting a year or so after its inception, by the delicate tones of tubular bells installed at the very height of the Ice Palace. Although the bells were an added expense for the sports clubs who spent half the year fundraising to put on the Carnival, they would have enchanted the tens of thousands of tourists that reportedly came from American and Europe to experience the joyful possibilities of winter in Montreal. But, after a smallpox epidemic in 1885 and public dissatisfaction with the increasing commercialisation in the event in the following years, the Carnival was no longer sustainable for its founding clubs, who now were left with a set of chimes that would not simply melt in the spring.

Enter St. Matthias’. In the 1880s, the Village of Cote-St-Antoine was growing. It had an elementary school with capacity for 200. It also had its own snowshoe club, a division of the St. George’s club that was so popular in Cote-St-Antoine that a permanent clubhouse was built, the site of today’s St. George’s School. Its 800 residents stepped out of their 125 houses to join many other athletic clubs, which found their places alongside fields, orchards, and lowing cattle. The same year that the school was built and the snowshoe club founded, 1886, 34-year-old Rev. Jervois Newnham took up the rectorship of St. Matthias’ after a brief stint at Onslow in Nova Scotia and a curacy at Christ Church Cathedral. He would become Bishop of Moosonee and later of Saskatchewan, and continued to be an avid snowshoer throughout his life, most notably snowshoeing 600 miles from Moose Factory to Toronto in 1901.

Although St. Matthias’ records don’t say, and your humble historian has not read Newnham’s diary (transcribed and published in 1943 by his sister-in-law, Mary Howard Shearwood), the theme of snowshoeing feels central to this story. Here is an avid snowshoer, member perhaps of the first snowshoeing club in the Village of Cote-St-Antoine, a former curate at the cathedral where the Ice Palace’s architect had gotten his start, and the rector of the most well-established church in one of the fastest-growing villages around Montreal – we might easily imagine such a person hearing that the chimes were to be decommissioned and being first in line to take them home.

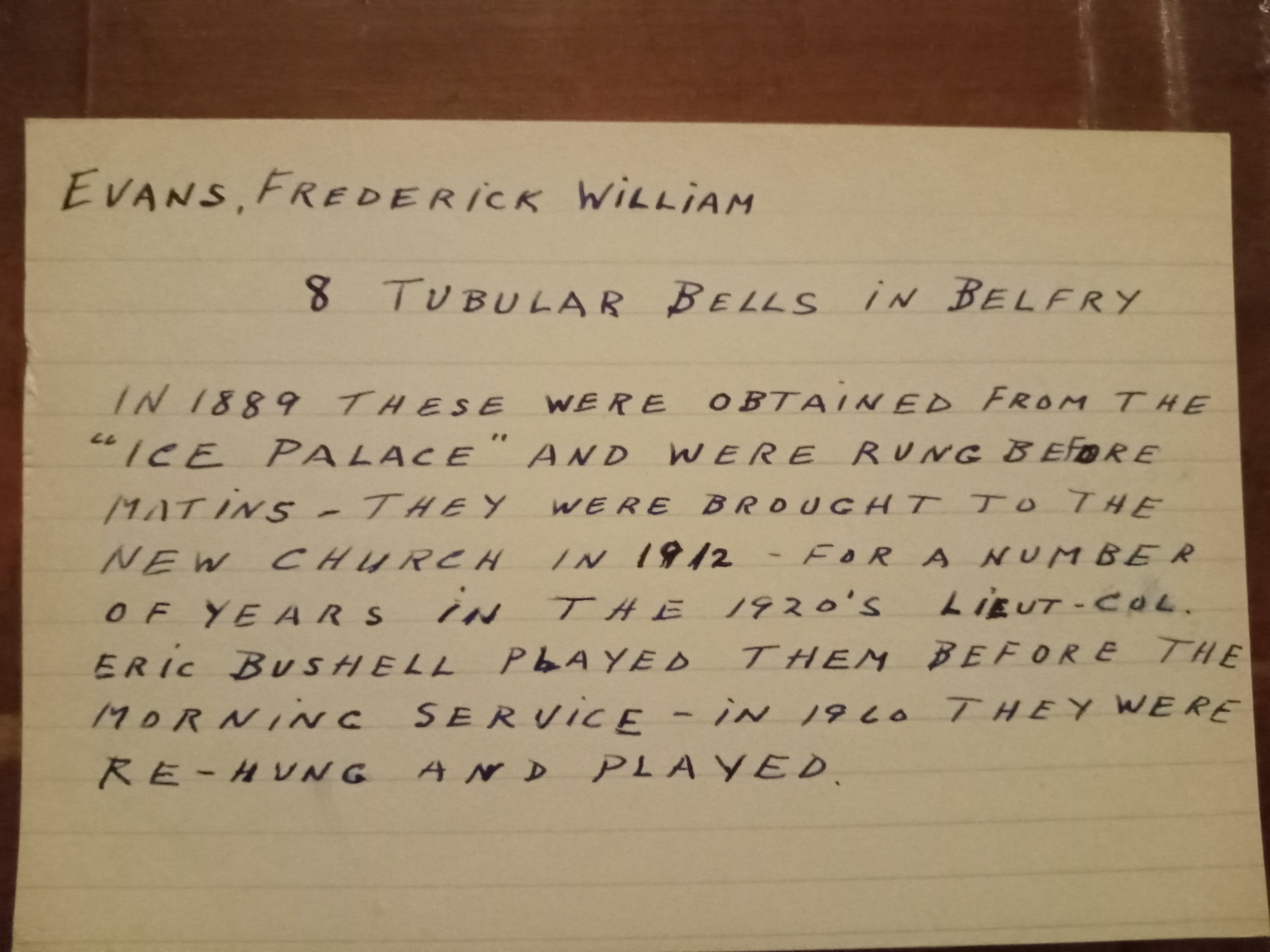

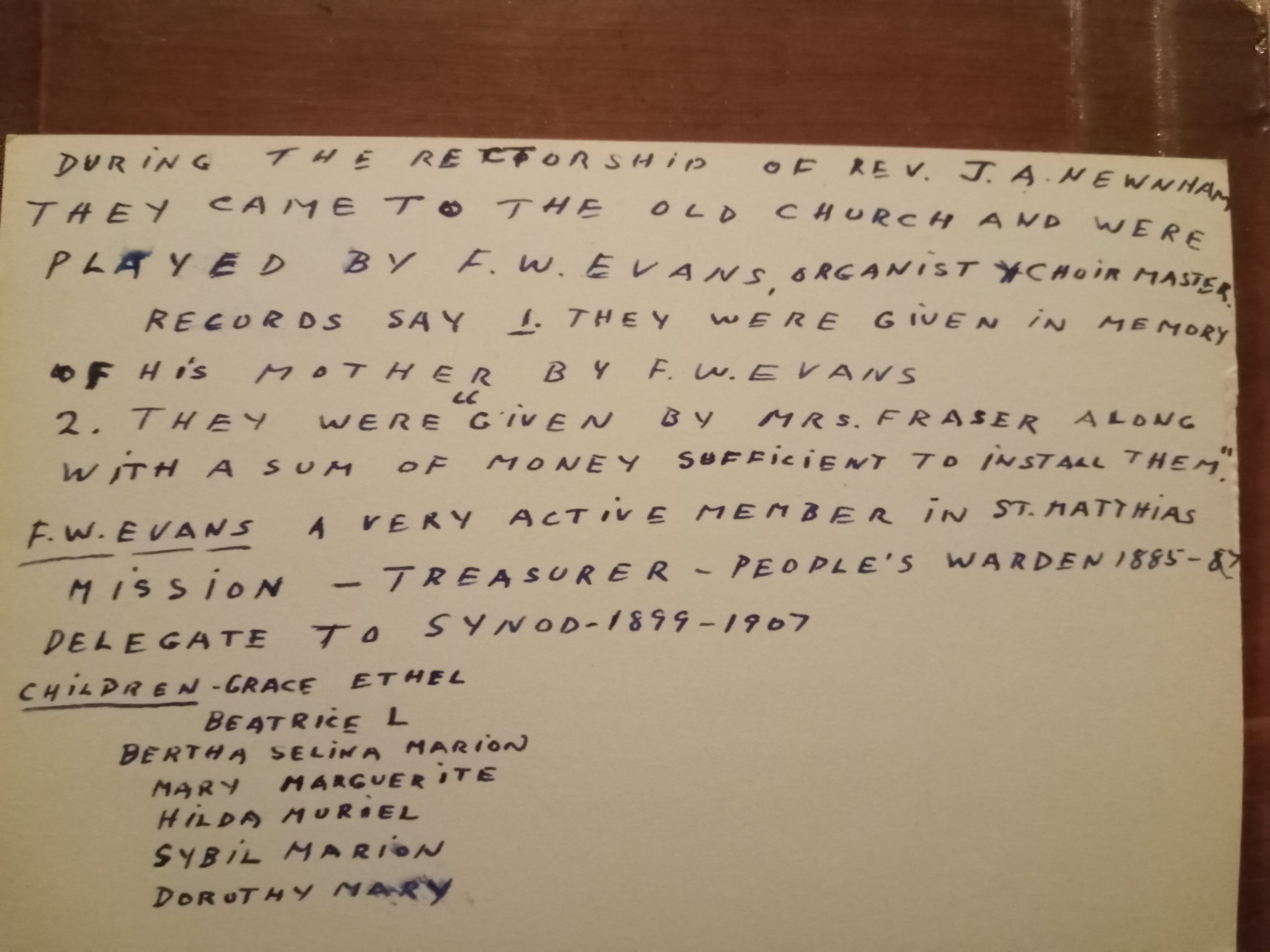

The chimes’ story does not end with Rev. Newnham’s snowshoeing connections – they still had to be purchased from the Carnival Committee, and there were necessarily installation costs. One of two people, per the inventory, paid: either the organist and choirmaster at the time, Frederick William Evans, in memory of his mother, or a certain Mrs. Fraser. Either way, Evans, who was just coming off a two-year stint as People’s Warden and would go on to be the parish’s Synod Delegate for almost a decade, played the chimes every Sunday thereafter. By all accounts, they could be heard throughout the Village, and perhaps even all the way into town.

The chimes came to the new building in 1912, and were played there by Eric Bushell, Rev. Bushell’s son and the St. Matthias’ organist for many years. They were rehung in 1960, but seem to have fallen into disuse thereafter, until a young server by the name of Mark Gallop rehung them once again in 1978, and played them on Sunday mornings for some time. Perhaps, when the ice begins to form again this winter, some new young person will take it upon themselves to rescue the chimes to once again peal over the streets of Westmount.